The strange history of the world's most stolen painting - Noah Charney

Throughout six centuries,

the Ghent Altarpiece

has been burned, forged,

and raided in three different wars.

It is, in fact, the world’s

most stolen artwork.

And while it’s told some of its secrets,

it’s kept others hidden.

In 1934, the police of Ghent, Belgium

heard that one of the Altarpiece’s panels,

split between its front and back,

was suddenly gone.

The commissioner investigated the scene

but determined that a theft

at a cheese shop was more pressing.

Twelve ransom notes appeared

over the following months

and one half of the panel was even

returned as a show of good faith.

Meanwhile, art restorer Jef van der Veken

made a replica of the other half

for display until it was found.

But it never was.

Some suspected that he was involved

in the theft and,

once ransom demands failed,

had simply painted over the original

and presented it as his copy.

But a definitive answer wouldn’t

come for decades.

Just six years later, Hitler was planning

a grand museum,

but was missing his most desired

possession: the Ghent Altarpiece.

As Nazi forces advanced, Belgian

leaders sent the painting to France.

But the Nazis commandeered

and moved it to a salt mine

converted into a stolen art warehouse

that contained over 6,000 masterpieces.

Near the war’s end in 1945,

a Nazi official decided he’d rather

blow up the mine

before letting it fall into Allied hands.

In fact, the Allies had soldiers

called Monuments Men

who were tasked with protecting

cultural treasures.

Two of them were stationed 570

kilometers away when one got a toothache.

They visited a local dentist,

who mentioned that his son-in-law

also loved art and took them to meet him.

They discovered that he was actually

one of the Nazi’s former art advisors,

now in hiding.

And miraculously, he told them everything.

The Monuments Men devised a plan

to rescue the art

and the local Resistance delayed

the mine’s destruction until they arrived.

Inside, they found the Altarpiece

among other world treasures.

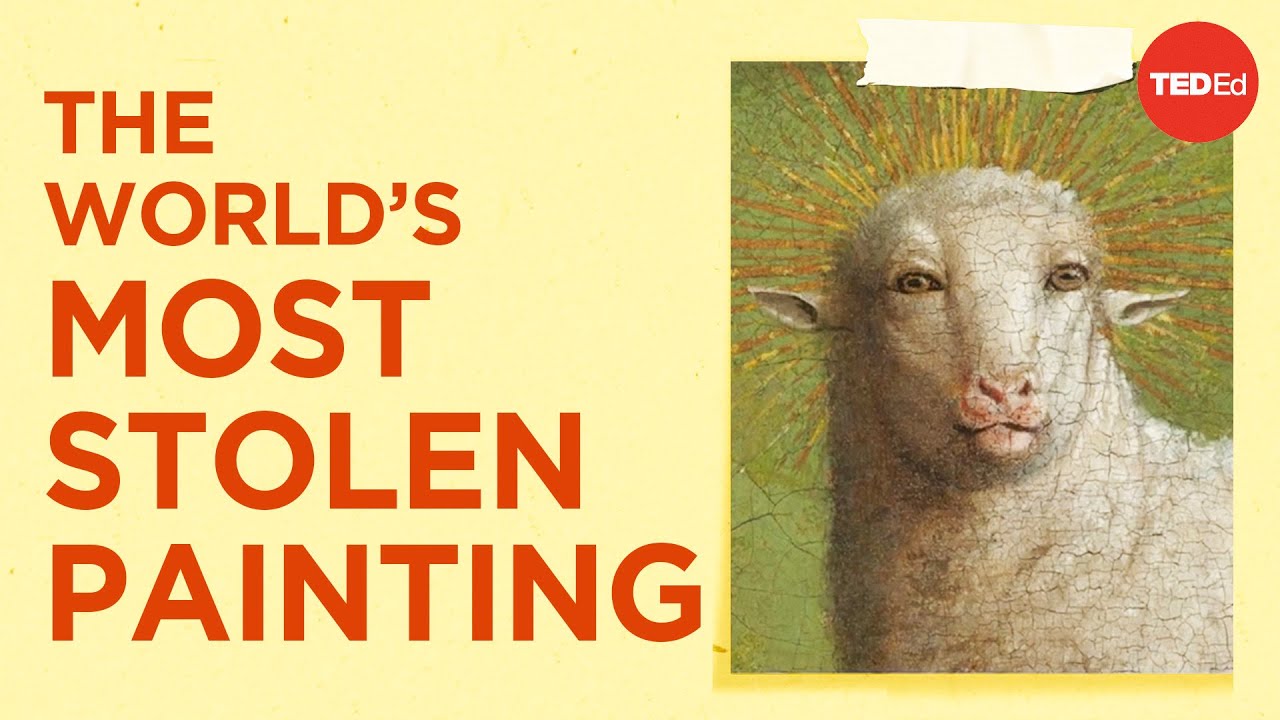

The Ghent Altarpiece,

also called "The Adoration of the Mystic

Lamb" after its central subject,

consists of 12 panels

depicting the Biblical story.

It’s one of the most influential artworks

ever made.

When Jan van Eyck completed

it in Ghent in 1432,

it was immediately deemed

the best painting in Europe.

For millennia, artists used tempera paint

consisting of ground pigment in egg yolk,

which created vivid but opaque colors.

The Altarpiece was the first to showcase

the unique abilities of oil paint.

They allowed van Eyck to capture

light and movement

in a way that had never been seen before.

He did this using brushes sometimes

as tiny as a single badger hair.

And by depicting details

like Ghent landmarks,

botanically identifiable flowers,

and lifelike faces,

the Altarpiece pioneered an artistic mode

that would come to be known as Realism.

Yet, conservation work completed

in 2019 found that, for centuries,

people had been viewing

a dramatically altered version.

Due to dozens of restorations,

as much as 70% of certain sections

had been painted over.

As conservators removed these layers

of paint, varnish, and grime,

they discovered vibrant colors and whole

buildings that had long been invisible.

Other details were more unsettling.

The mystic lamb’s four ears

had long perplexed viewers.

But the conservation team

revealed that the second pair

was actually a pentimento—

the ghost of underlying layers of paint

that emerge as newer ones fade.

Restorers had painted

over the original lamb

with what they deemed

a more palatable version.

They removed this overpainting

and discovered the original to be

shockingly humanoid.

The conservators also finally determined

whether van der Veken

had simply returned the missing panel

from 1934.

He hadn’t.

It was confirmed to be a copy,

meaning the original is still missing.

But there was one final clue.

A Ghent stockbroker, while on his deathbed

a year after the theft,

revealed an unsent ransom note.

It reads:

it “rests in a place where neither I,

nor anybody else,

can take it away without arousing

the attention of the public.”

A Ghent detective remains assigned

to the case but,

while there are new tips every year,

it has yet to be found.