The fundamentals of space-time: Part 2 - Andrew Pontzen and Tom Whyntie

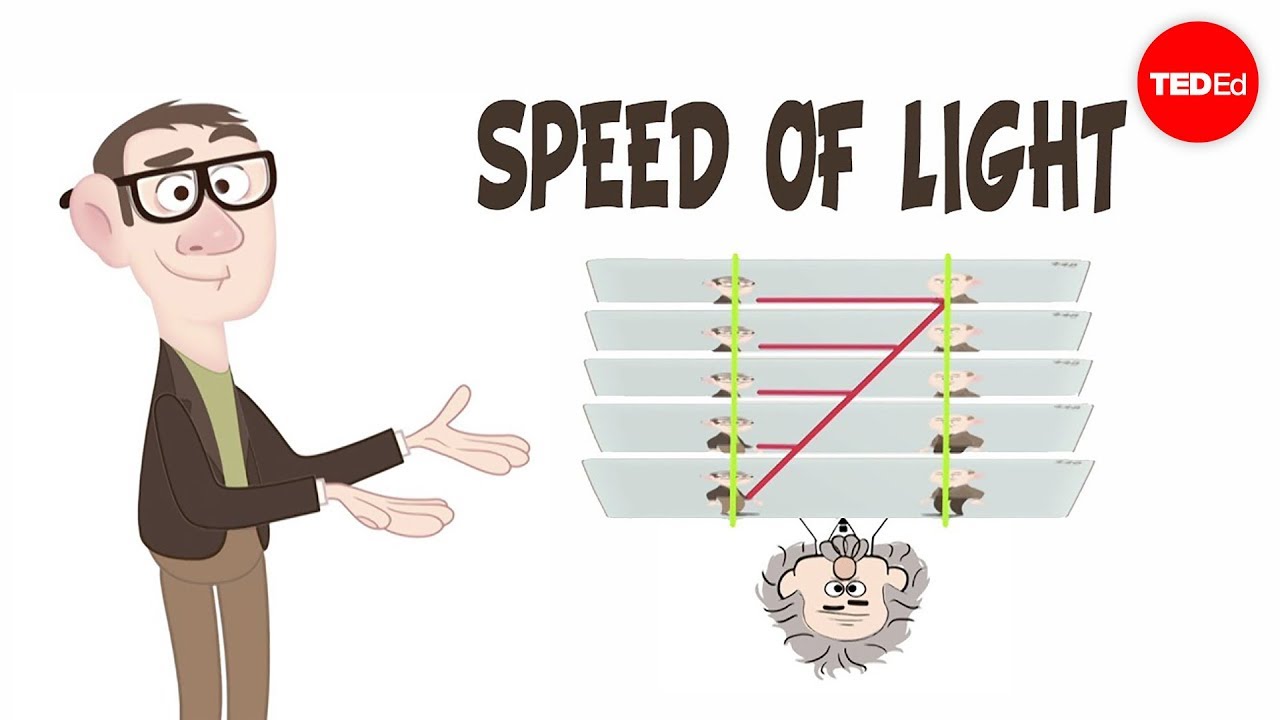

Light: it's the fastest thing in the universe,

but we can still measure its speed

if we slow down the animation,

we can analyze light's motion using

a space-time diagram,

which takes a flipbook of animation panels,

and turns them on their side.

In this lesson, we'll add the single experimental fact

that whenever anyone measures just how fast light moves,

they get the same answer:

299,792,458 meters every second,

which means that when we draw light

on our space-time diagram,

it's world line always has to appear at the same angle.

But we saw previously that speed,

or equivalently world line angles,

change when we look at things from

other people's perspective.

To explore this contradiction,

let's see what happens if I start moving

while I stand still and shine the laser at Tom.

First, we'll need to construct the space-time diagram.

Yes, that means taking all of

the different panels showing the different moments in time

and stacking them up.

From the side, we see the world line

of the laser light at its correct fixed angle,

just as before.

So far, so good.

But that space-time diagram represents Andrew's perspective.

What does it look like to me?

In the last lesson, we showed

how to get Tom's perspective moving all the panels

along a bit until his world line is completely vertical.

But look carefully at the light world line.

The rearrangement of the panels

means it's now tilted over too far.

I'd measure light traveling faster than Andrew would.

But every experiment we've ever done,

and we've tried very hard,

says that everyone measures light to have a fixed speed.

So let's start again.

In the 1900s, a clever chap named Albert Einstein

worked out how to see things properly,

from Tom's point of view,

while still getting the speed of light right.

First, we need to glue together the separate panels

into one solid block.

This gives us our space-time,

turning space and time into

one smooth, continuous material.

And now, here is the trick.

What you do is stretch your block of space-time

along the light world line,

then squash it by the same amount,

but at right angles to the light world line,

and abracadabra!

Tom's world line has gone vertical,

so this does represent the world from his point of view,

but most importantly,

the light world line has never changed its angle,

and so light will be measured by Tom

going at the correct speed.

This superb trick is known as

a Lorentz transformation.

Yeah, more than a trick.

Slice up the space-time into

new panels and you have

the physically correct animation.

I'm stationary in the car,

everything else is coming past me

and the speed of light

works out to be that same fixed value

that we know everyone measures.

On the other hand,

something strange has happened.

The fence posts aren't spaced a meter apart anymore,

and my mom will be worried

that I look a bit thin.

But that's not fair. Why don't I get to look thin?

I thought physics was supposed to be the same

for everyone.

Yes, no, it is, and you do.

All that stretching and squashing

of space-time has just muddled together

what we used to think of separately

as space and time.

This particular squashing effect

is known as Lorentz contraction.

Okay, but I still don't look thin.

No, yes, you do.

Now that we know better about space-time,

we should redraw

what the scene looked like to me.

To you, I appear Lorentz contracted.

Oh but to you, I appear Lorentz contracted.

Yes.

Uh, well, at least it's fair.

And speaking of fairness,

just as space gets muddled with time,

time also gets muddled with space,

in an effect known as time dilation.

No, at everyday speeds,

such as Tom's car reaches,

actually all the effects are much, much smaller

than we've illustrated them.

Oh, yet, careful experiments,

for instance watching the behavior of tiny particles

whizzing around the Large Hadron Collider

confirmed that the effects are real.

And now that space-time is

an experimentally confirmed part of reality,

we can get a bit more ambitious.

What if we were to start playing

with the material of space-time itself?

We'll find out all about that in the next animation.