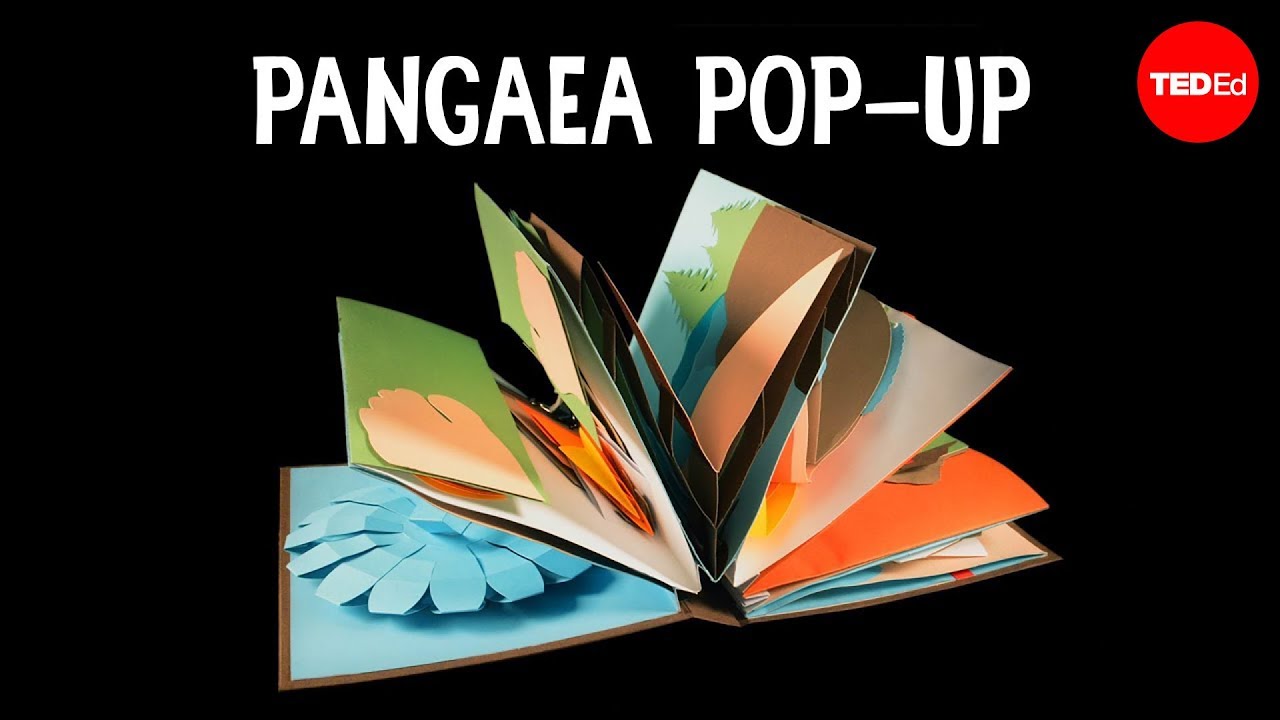

The Pangaea Pop-up - Michael Molina

Once upon a time,

South America lived harmoniously alongside Africa

until a crack in the Earth

drove the two continents apart.

This breakup began about 200 million years ago

during the separation of the supercontinent

known as Pangaea.

Their proximity back then

explains why the same plant fossils and reptile fossils,

like the Mesosaurus,

can be found on the South American east coast

and African west coast.

However, this evidence does not account

for how the continents moved apart.

For that, we'll need to take a close look

at the earth below our feet.

Though you may not realize it,

the ground below you is traveling across the Earth

at a rate of about 10 cm/year,

or the speed at which your fingernails grow.

This is due to plate tectonics,

or the large-scale movement of Earth's continents.

The motion occurs within the top two layers

of the Earth's mantle,

the lithosphere and asthenosphere.

The lithosphere,

which includes the crust and uppermost mantle,

comprises the land around you.

Beneath the lithosphere

is the asthenosphere

the highly viscous but solid rock portion

of the upper mantle.

It's between 80 and 200 km

below the Earth's surface.

While the asthenosphere wraps around the Earth's core

as one connected region,

the lithosphere is separated on top

into tectonic plates.

There are seven primary tectonic plates

that compose the shape of the planet we know today.

Like the other smaller tectonic plates,

the primary plates are about 100 km thick

and are composed of one or two layers:

continental crust and oceanic crust.

Continental crust forms the continents

and areas of shallow water close to their shores,

whereas oceanic crust forms the ocean basins.

The transition from the granitic continental crust

to the basaltic oceanic crust

occurs beyond the continentel shelf,

in which the shore suddenly slopes down

towards the ocean floor.

The South American Plate is an example

of a tectonic plate made of two crusts:

the continent we know from today's map

and a large region of the Atlantic Ocean around it.

Collectively comprising the lithosphere,

these plates are brittler and stiffer

than the heated, malleable layer of the asthenosphere below.

Because of this,

the tectonic plates float on top of this layer,

independently of one another.

The speed and direction in which these tectonic plates move

depends on the temperature and pressure

of the asthenosphere below.

Scientists are still trying to nail down

the driving forces behind this movement,

with some theories pointing towards mantle convection,

while others are examining

the influence of the Earth's rotation

and gravitational pull.

Though the mechanics have not been sorted out,

the scientific community agrees

that our tectonic plates are moving

and have been for billions of years.

Because these plates move independently,

a fair amount of pushing and pulling

between the plates occurs.

The first type of interaction

is a divergent boundary,

in which two plates move away from one another.

We see this in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

between South America and Africa.

The next interaction is when two plates collide,

known as a convergent boundary.

In this instance, the land is pushed upward

to form large mountain ranges,

like the Himalayas.

In fact, the Indian Plate is still colliding

with the Eurasian Plate,

which is why Mount Everest

grows one cm/year.

Finally, there's the transform boundaries,

where two plates scrape past one another.

The grinding of the transform boundary

leads to many earthquakes,

which is what happens

in the 810 mile-long San Andreas Fault.

The moving Earth is unstoppable,

and, while a shift of 10 cm/year may not seem like a lot,

over millions of years our planet will continue

to dramatically change.

Mountains will rise,

shorelines will recede,

islands will pop up.

In fact, one projected map shows

the cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco

on top of each other.

Maybe South America and Africa

will come together again, too.

Only time will tell.